In an abstract presented at The Australian Sociological Association Conference, November 26, 2021 the relationship between science policy in New Zealand; the decision-making practices of funding committees and the funding outcomes of scientists were explored. The conference abstract was titled Innovation and Ignorance: How Science Funding Schemes Deter the Production of Uncomfortable Knowledge.

The presentation followed a Masters research project . The research project sought to understand why there was no policy in New Zealand aimed at stewarding endocrine disrupting chemicals; to limit EDC exposures, and protect the health of both humans and natural ecosystems. The risk of EDCs has been identified for over 20 years, and for roughly the same period, governments, including the USA and Europe have developed policies aimed at guiding regulation. Yet no quorum of scientists could be located in New Zealand with experience in EDC research that could advocate for such a policy. New Zealand was silent on the matter.

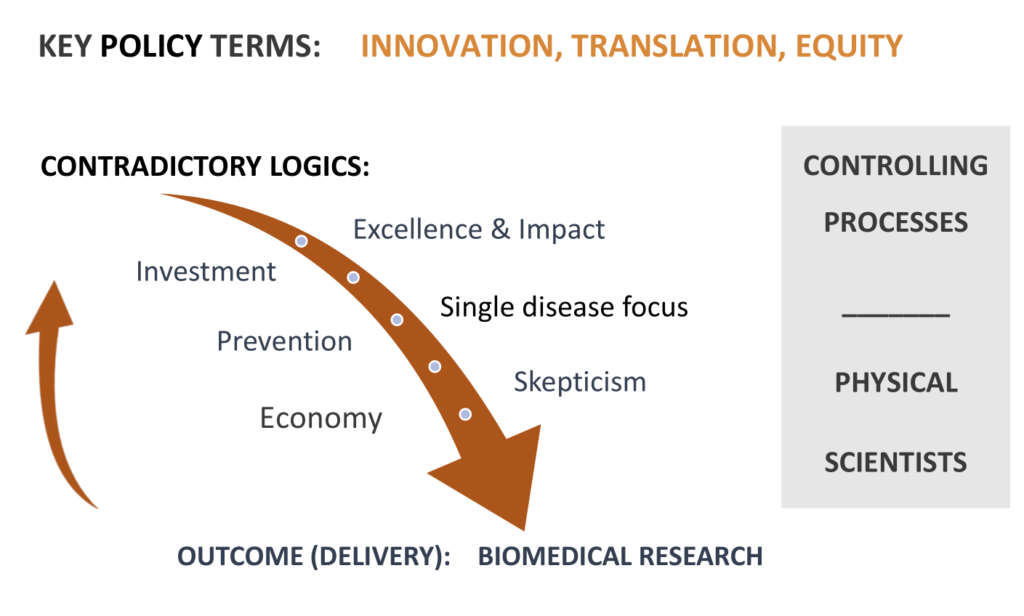

In analysing government policy, and through interviews with scientists, I identified that political, economic, cultural and social factors co-produce funding environments which privilege certain institutional actors while stymying others.

Interviews with scientists revealed that the policy environment emphasises innovation and science excellence. These terms on the surface appear responsible, yet in hypercompetitive funding environments, non ‘innovative’ and non-normative science is viewed as risky and uncertain. Therefore, funding committees tend to downgrade research proposals not clearly identified as innovative or excellent.

Key terms in science policy direct funding committees to flag or dismiss research projects. Scientists in health research compete for funding in highly (ultra) competitive funding environments, if they do not fulfil policy requirements, they will be downgraded and unlikely to be funded. Policy terms and ultracompetitive funding environments were important controlling processes pushing uncertain upstream science, down the list for consideration.

Innovation

Innovation has been a key policy term in applied in New Zealand science policy for 20 years and innovation priorities influence the allocation of funding.

At first glance, the term ‘innovation’ and innovative science is ordinarily viewed as positive – as progressive. However, the term, when applied by international (such as the OECD) institutions, is explicit, it doesn’t loosely mean innovation (as novelty or creativity), but explicitly associates the term with economic production.

OECD 2005: “the implementation of a new or significantly improved product (good or service) or process, a new marketing method, or a new organisational method in business practices, workplace organisation or external relations”

Link to re-recording post event.

Interviews for the research project identified that participant scientists operated with different logics – and those that focused on biomedical drug development (innovation opportunities) were more likely to be funded.

The ‘looking upstream’ scientists were rarely able to secure research funding. They were often highly creative in the work they sought to undertake. They were looking beyond a single disease, or single exposure and frequently engaging in in interdisciplinary research, and applying analytical technologies in novel ways. Their idea of prevention was preventing disease from starting in the first place, they were focussed on the primordial form of disease prevention. They saw their work as having the potential to impact upstream policy.

The scientists who found it easier (it is never easy) to secure research funding, understood that they were helping drive biomedical, or drug development. These ‘biomedical’ scientists acknowledged (and hoped) that their research would end in discovery that would hopefully contribute to primary prevention, as a cure in the early stages of disease development, and perhaps prevent suffering. Many of these scientists spent a significant part of their time applying for research funding, and were simply relieved that they could continue to research, and fund their staff and post graduate students.

Therefore, health research funding was predominantly directed to innovative projects that were intended to result in the production of a biomedical application or medical intervention that would be rolled out inside the health sector.

Importantly, both forms of science were not equivalently funded. Biomedical research dwarfs environmental and human health research into the drivers of disease.

Medical equity is not the same as health equity.

Research funding prioritising innovation and single disease norms (which link with excellence in disciplinary sectors in scientific research) would be unlikely to provide evidence to build support for policy development that could challenge the social and economic drivers of disease that are embedded in political, civic and economic activity. Innovation oriented research funding was oriented to deal with disease as it arose in the human body, as a consequence of participating in daily life. It was inherently medicalised, did not address the ethical antinomies of polypharmacy.

As I note in the presentation, ‘A medicalised perspective fails to draw attention to issues of justice and equity. It assumes that the person on 3 medications can add another 7 medications. Medical equity is different from health equity. Medical equity implies that as long as someone suffering from the diseases of poverty is treated equally inside the health system – it is Ok. This disregards the suffering inherent in multimorbidity, and the pervasive health effects of polypharmacy.’

The acceleration of chronic diseases and deficiencies (which directly increase risk for infectious disease) explicitly should create a national effort that requires researchers and policymakers to look upstream to structural drivers of disease. Genetics play a very small role, less than 15%, in driving disease. Yet, for physical (basic) scientists operating in the current policy environment – funding for this upstream work is almost impossible.

Endocrine disruption appears to be co-driver of many diseases and disorders, including metabolic disease, cancer and neurodevelopmental disorders. Metabolic diseases are predominantly driven by obesogenic environments that inherently privilege low quality, ultraprocessed foods, and a failure of government policy to address the structural drivers (as market failure) at a high level. The vast majority of chronic disease in new Zealand is amplified by poverty and inequality. Obesity and multimorbidity are more closely associated with low income status. Multimorbidity is more common, while single disease status’ is less common. Driving forces produce overlaping and produce cascading effects throughout the body, often driven by environmentally driven inflammation. Chronic diseases tied to environmental exposures and nutritional deficiencies are being increasingly observed in babies and children in New Zealand.

Institutional entrapment

Health research should be targetted to protecting and improving health, as required by the signatories to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). A medicalised perspective cannot achieve this. First, it ‘naturally’ medicalised researchers and scientists, as funding was directed to biomedical applications that would be translatable inside the health sector. Second, the policy environment produced barriers to scientists aiming to produce what has been refered to by Steve Rayner as ‘uncomfortable knowledge‘. This is knowledge that may potentially reveal human and environmental harms from institutional and economic activity. This knowledge may then produce policy-relevant information that could impact that activity.

For 30 years universities have operated as semi-privatised quasi-government institutions, pitching themselves in competitive environments, to secure the best students, and to secure funding for research projects that might also result in lucrative IP. In modern universities, the institutions that have grown more rapidly are those that have potential to produce income streams, such as the STEM sciences.

The private-public relationships become embedded conflicts of interest. They make research that has potential to conflict with the research priorities and the aims of partners (such as large multinationals), or which may potentially criticise the development of new technologies or criticise the emissions or breakdown products of those technologies – as unlikely. In these environments, research drawing attention to environmental and health harms is often sporadic, piecemeal and poorly funded.

The effect of not funding upstream research produces and perpetuates ignorance in the socio-political and scientific demosphere – shrinking the evidence base that should unite scientists, policy makers, the public and build political licence – which might then result in public interest regulation of those upstream drivers. This is predominantly not the fault of the individual scientists nor funding committees. It is shaped by the institutions that control science funding and shape science policy, and the effect of hypercompetitive funding environments that drive conservatism in decision-making, and result in cultures that are risk avoidant.

Yes, these are wicked problems, but an obligation to ensure the resilience of the New Zealand public through the protection of health, is embedded in the very legislation that gives the New Zealand government its powers. Protection of health has roots in the origins of nation-state and citizen contracts, that the state will govern, and in return the citizens will be safe, they will be protected. Policy that privileges IP cannot achieve this alone.

The government ‘just’ needs to shape policy in order to fulfil these stated aims.